CMake

Brief

To understand modern CMake you need to understand targets. Basically a target is an executable or a library. You will define a target for your executable and describe its source files, and then you will import the targets for each library you use, and will add those targets as a dependency of your executable. Here is an example:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.8)

project(p6-hello-world)

add_executable(${PROJECT_NAME} # Creates a target called ${PROJECT_NAME}, a.k.a. p6-hello-world

src/main.cpp # And adds its source files: main.cpp and something.cpp

src/something.cpp # Note that you don't need to list the header files here (.h / .hpp)

)

target_include_directories(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE src) # Directory containing our header files

add_subdirectory(p6) # Includes the p6 library; this assumes that you have a folder called p6 at the same level as this CMakeLists.txt file, and that the p6 folder contains a CMakeLists.txt file.

target_link_libraries(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE p6::p6) # Adds the target "p6::p6" as a dependency of our target ${PROJECT_NAME}. Unfortunately the command is called target_link_libraries() even though it can be used for other things than just linking; don't get confused! A better name would have been add_dependency()

# The name of the target "p6::p6" is up to the library authors. Check out their documentation to know how they called it!

# The "::" in the name of the library's target is not mandatory, but library authors often add it because target_link_libraries() can do many different things, and if you make a typo in the name of the target it will ignore it instead of reporting an error. It is only if you have a "::" in the name that target_link_libraries() will know that it can't be anything but a target and will raise an error if the name doesn't actually correspond to a target.

And that is all you need for a basic CMakeLists.txt!

If all your libraries define a target properly then you don't need anything more to build your project. (If they don't, unfortunately you will have to do their job for them).

CMake tips

Now we will see a few useful things that you can do with CMake:

Setting your C++ version

You can ask for a specific version of C++:

target_compile_features(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE cxx_std_20)

(If you don't you will probably get C++11 by default).

You can even ask for finer details with parameters like cxx_variadic_templates. This can be useful to increase the portability of your code a little bit (for example if you need C++11 plus only one little feature from C++14). Don't abuse it though because it can be very tedious to maintain!

GLOB

If you don't want to have to list all your .cpp files manually in your CMakeLists.txt you can use

file(GLOB_RECURSE MY_SOURCES CONFIGURE_DEPENDS src/*)

It will grab the list of all .cpp files in src ant put then in MY_SOURCES.

GLOB_RECURSEmeans that it will also find the files that are in the subdirectories of src. If you only want to find the files at the first level of src you can useGLOBinstead.CONFIGURE_DEPENDSmeans that CMake will check before every build to see if files were added or deleted, and if so it will update accordingly. Without it you would need to manually tell CMake to reconfigure each time you add or remove a file.

You can then use that list of files like so:

add_executable(${PROJECT_NAME} ${MY_SOURCES})

warning

Every CMake expert will tell you that you should never use file(GLOB) or file(GLOB_RECURSE). The reason is always the same and can be found in the official CMake documentation:

We do not recommend using GLOB to collect a list of source files from your source tree. If no CMakeLists.txt file changes when a source is added or removed then the generated build system cannot know when to ask CMake to regenerate. The

CONFIGURE_DEPENDSflag may not work reliably on all generators, or if a new generator is added in the future that cannot support it, projects using it will be stuck. Even ifCONFIGURE_DEPENDSworks reliably, there is still a cost to perform the check on every rebuild.

I disagree with it though, since to me maintaining a list of my .cpp files in my CMakeLists.txt is more of a hassle than having to refresh CMake manually when I add or remove a file. (And CONFIGURE_DEPENDS makes it even less of a hassle).

Now that you have the arguments from both sides, pick your poison.

tip

If it is hard to add new files to your codebase people will tend to try and avoid it, and will put more things in one single file, which might not be desirable. If you want to encourage people to write many small files, using GLOB_RECURSE might be a good idea 😉

Adding libraries

In order to make sure that anybody cloning your repository will have all the required libraries to compile your project, it is important to have a way to automatically download them. Submodules are one way of achieving this, but in the case of external libraries that you are not actively writing yourself (which should be most of the cases, especially if you are a beginner programmer), then submodules are a bit annoying and don't bring any value. In that case, CMake offers a better alternative: FetchContent. It will automatically download the libraries when necessary:

include(FetchContent) # Include the FetchContent functions. Only do this once, even if you import several libraries

FetchContent_Declare( # Declare a library: its name and where to find it

p6 # Name of the library

GIT_REPOSITORY https://github.com/julesfouchy/p6 # Repo of the library

GIT_TAG 8346d1e27567815bb9b231cf3ecbfaf1e3bd832a # Exact commit hash that you want to use

)

FetchContent_MakeAvailable(p6) # Download the library

target_link_libraries(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE p6::p6) # Link the library as usual

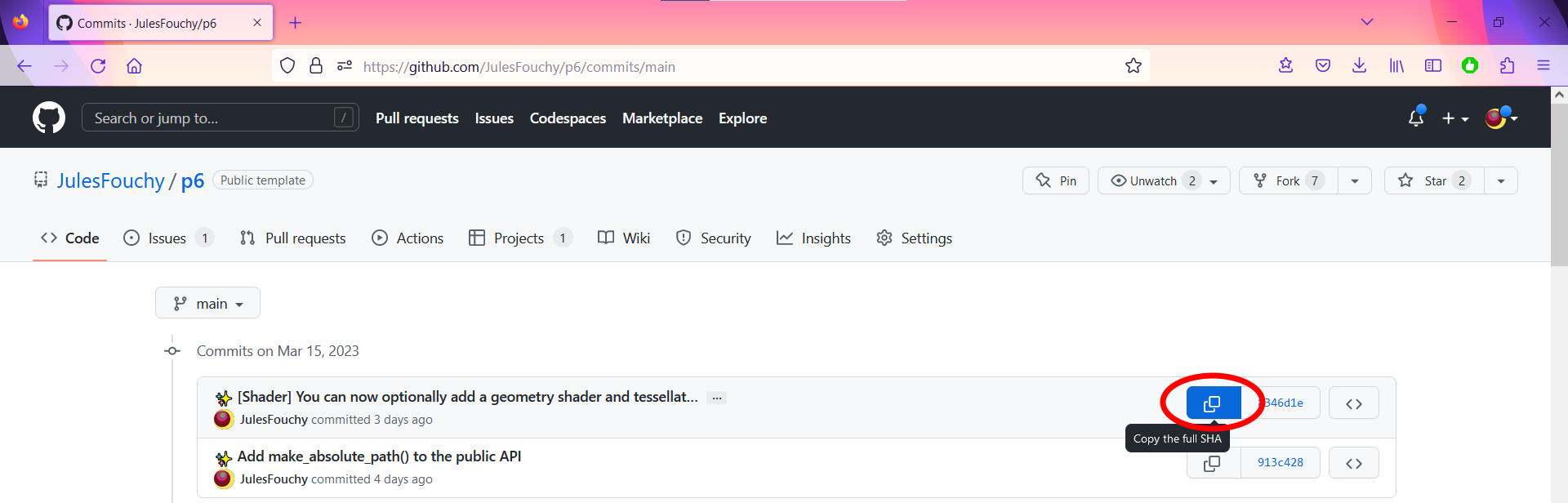

You can find the hash of a commit on GitHub / GitLab: (by default choosing the latest commit should be fine):

Enabling warnings

if (MSVC)

target_compile_options(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE /WX /W4)

else()

target_compile_options(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE -Werror -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -pedantic-errors -Wimplicit-fallthrough)

endif()

/WX and -Werror make your compiler treat warnings as errors, and the other flags enable a lot of useful warnings.

tip

Warnings are your friends. They exist to protect you from bad practices and bugs. Listen to them!

A C++ code that compiles is far from guaranteed to have no bugs! (mostly because of backward compatibility with C). This is why warnings are important!

caution

If you are writing a library, using warnings as errors can prevent your users from compiling your library. Since the different compilers (and compiler versions) don't generate the same warnings, you might have missed some.

You should only enable warnings as errors when you are building the tests of your library, and disable it by default for your users. This is what p6 does:

set(WARNINGS_AS_ERRORS_FOR_P6 OFF CACHE BOOL "ON iff you want to treat warnings as errors")

if (WARNINGS_AS_ERRORS_FOR_P6)

if(MSVC)

target_compile_options(p6 PRIVATE /WX /W4)

else()

target_compile_options(p6 PRIVATE -Werror -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic -pedantic-errors -Wconversion -Wsign-conversion)

endif()

target_include_directories(p6 PUBLIC include)

else()

target_include_directories(p6 SYSTEM PUBLIC include) # When warnings are disabled, we use the SYSTEM option of target_include_directories: this tells the compiler to ignore any warnings coming from the `include` directory.

endif()

set(WARNINGS_AS_ERRORS_FOR_P6 ON)

add_subdirectory(p6)

Ignoring warnings from external code

Warnings are great, but warnings coming from third-party libraries that you did not write are just a nuisance. Luckily, there is a way to disable them!

target_include_directories(${PROJECT_NAME} SYSTEM PRIVATE some_lib/include)

The SYSTEM option of target_include_directories tells the compiler to ignore any warnings coming from headers in the some_lib/include directory.

Adding #define (compile definitions)

You can #define SOMETHING from CMake. This can be useful to propagate information from CMake into your project. For example you can do

target_compile_definitions(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE

USE_THIS_FEATURE

)

#if USE_THIS_FEATURE

// Do something

#else

// Do something else

#endif

A very good use case is

target_compile_definitions(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE

$<$<CONFIG:Debug>:DEBUG>

)

which defines DEBUG if you are building in debug mode. (This uses a generator expression. It can be read as: "If the CMake CONFIG is Debug, then return DEBUG, otherwise return nothing"). You can then have debug checks in your code that are only compiled in debug mode and totally removed in release:

void assert_shader_is_bound(GLint id)

{

#if DEBUG

GLint current_id;

glGetIntegerv(GL_CURRENT_PROGRAM, ¤t_id);

assert(current_id == id && "The shader is not bound");

#endif

}

You can also give a value to your #define (by default it gets the value 1):

target_compile_definitions(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE

WINDOW_NAME=\"Django ${CMAKE_PROJECT_VERSION}\"

)

glfwCreateWindow(1280, 720, WINDOW_NAME, nullptr, nullptr);

// Which expands to:

glfwCreateWindow(1280, 720, "Django 1.0", nullptr, nullptr);

Setting the output path

By default your executable will end up in build with many other stuff generated by CMake. You can change that with the target property RUNTIME_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY. I personnaly like to do

set_target_properties(${PROJECT_NAME} PROPERTIES

RUNTIME_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY ${CMAKE_SOURCE_DIR}/bin/${CMAKE_BUILD_TYPE})

which gives me

├── bin/

│ ├── Debug

│ │ ├── myproject.exe // Built in debug mode

│ │ └── ...

│ └── Release

│ ├── myproject.exe // Built in release mode

│ └── ...

├── build/

│ ├── random cmake stuff you don't need to care about

│ └── ...

├── src/

│ ├── ...

│ └── ...

└── CMakeLists.txt

Copying files and folders

Very often in projects you need to have files available alongside your executable; it can be images, 3D models, shaders: anything that is not built into your binary but instead loaded at runtime.

You will have those files somewhere in your sources, but when you produce an executable and send it to your friends you must not forget to send the other resource files as well! CMake can help you by automating the process of copying these files to the output folder where your executable is created.

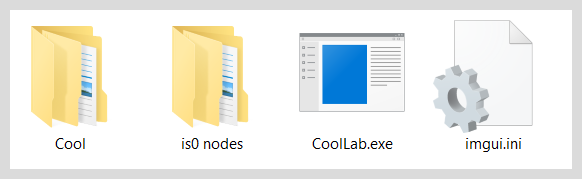

All the files required by CoolLab.exe

There is no straight-forward of asking CMake to do it1, but you can use this great library.

Precompiled header

A precompiled header is pretty useful (see Precompiled Header).

You can create one with CMake using target_precompile_headers:

target_precompile_headers(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE

<vector>

<string>

<memory>

<functional>

<imgui/imgui.h>

<imgui/misc/cpp/imgui_stdlib.h>

<Cool/Log/Log.h>

)

CMake for library authors

As a library, your CMakeLists.txt has one goal: define a target containing all the required information for people to link to your library. Users should only have to do

add_subdirectory(libname)

target_link_libraries(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE libname::libname)

This is possible because a target can store a lot of things: the sources, the include directories, the compile definitions, etc. (this information is known as requirements in the literature). When users call target_link_libraries(${PROJECT_NAME} PRIVATE libname::libname) all this information is propagated to ${PROJECT_NAME} by CMake so that our main target will get the proper includes and so on.

If you want to have a look at a real-world example of modern cmake, check out p6 (small library) or Cool (big framework).

add_library()

You create your library's target with

add_library(libname)

(It is the equivalent of add_executable(exename).)

Use the target_xxx() commands

To set requirements of your library, always use a target_xxx function. They all have alternatives without the target_ prefix, but those functions affect the global state instead of just your target, which is obviously bad! For example if your project uses libA and libB, you don't want libB to see the include directories and settings of libA! These libraries should be completely independent!

They are all used like so:

target_xxx(target_name PRIVATE additional_parameters ...)

You can also use PUBLIC or INTERFACE instead of PRIVATE (see PRIVATE | PUBLIC | INTERFACE).

Here are the most important functions:

target_include_directoriesSpecifies the location of the include files. For a library I would suggest to put them in a include/libname folder and to dotarget_include_directories(libname PUBLIC include)so that the include files are accessed with#include <libname/some_file.hpp>. It can also be nice to add alibname.hppfile that includes all the other header files. It allows users to include the whole library at once with#include <libname/libname.hpp>.target_sourcesAdds source files to the target (appends to the list that was already set withadd_library(libname some_file.cpp)). It can be useful for example if you only need some files in some situations:

add_library(Cool src/Cool.cpp)

if (USE_OPENGL)

target_sources(Cool PRIVATE src/OpenGL/opengl.cpp)

elseif (USE_VULKAN)

target_sources(Cool PRIVATE src/Vulkan/vulkan.cpp)

endif()

target_link_librariesTo add another target as a dependency.target_compile_optionsWe have seen it in Enabling warnings.target_compile_featuresWe have seen it in Setting your C++ version.target_compile_definitionsWe have seen it in Adding#define(compile definitions).target_precompile_headersWe have seen it in Precompiled header.

PRIVATE | PUBLIC | INTERFACE

This is the visibility of the requirements set with target_xxx().

PRIVATE: Only this target will have access to these requirements. When other targets link to this one withtarget_link_libraries()they will not get the private requirements. For example your warning level should always be private because you do not want to impose it on your dependents:target_compile_options(libname PRIVATE -Werror -Wall)PUBLIC: This target and all of its dependents will be able to access the public requirements. For example if some include directories are used both internaly and by users to access the library, then they should be public:target_include_directories(libname PUBLIC include)Also if you use some other library in your headers, then it will be visible by your users when they include your header, so you need to provide your users with the library:

target_link_libraries(Cool PUBLIC glad)INTERFACE: This target will not have access to these requirements but its dependents will. It is a bit peculiar but can be used for example in a header-only library: the library itself does not need to see the include directory (since there is no source files at all to build), but the dependents do:target_include_directories(my-header-only-lib INTERFACE include)This can also be used if the user-facing headers are different from the private ones (e.g. if you have many headers but only want users to see a

libname.hppheader that includes all the other ones):target_include_directories(libname INTERFACE include) # The include folder is only used by users and only contains libname.hpp

target_include_directories(libname PRIVATE src) # All the headers that we use internally are in src (alongside the .cpp)

tip

Try to keep things private as much as possible! Don't pollute others for no reason.

Add an alias containing "::"

add_library(p6)

add_library(p6::p6 ALIAS p6)

People care about having a name with :: because target_link_libraries() can do many different things and if you make a typo in the name of the target it will ignore it instead of reporting an error. It is only if you have a :: in the name that target_link_libraries() will know that it can't be anything but a target and will raise an error if the name doesn't actually correspond to a target.

As far as the alias name goes, people have different conventions like p6::p6, p6::core etc. Pick one that you like.

Going further

Going Further

- The default functions available in CMake don't quite do what we want. They copy the files only once, when the CMakeLists.txt file is run. They won't re-copy them automatically whenever they change.↩